|

One of the most notable issues in Langan and Morton’s research was their positionality and the absence of identifying their positionality at the start of their research. Wamba uses Maher and Tethreault’s (2001) definition of positionality, which “is the idea of people not being defined in terms of fixed identities, but rather by their location within shifting networks of relationships that can be analyzed and changed” (Wamba 2017). Ultimately by not clearly stating their positionality at the beginning of the research to themselves and to the stakeholders, Langan and Morton jeopardized their whole research project. As a budding researcher, Langan and Morton’s calamitous research story heeds as a warning. It is clear that identifying one’s own positionality is essential to the research process. Wamba writes “Action researchers concern themselves with positionality because it helps them reflect on trustworthiness, research ethics, solidarity around issues, and motivation into action” (Wamba 2017). By reflecting on my positionality during action research, I will be cognizant of the reasons for the actions I take and opinions I form.

Works Cited: Langan, D., & Morton, M. (2009). Reflecting on community/academic ‘collaboration’: The challenge of ‘doing’ feminist participatory action research. [Article]. Action Research, 7(2), 165-184. doi: 10.1177/1476750309103261 Wamba, N. (2017). Inside the Outside: Reflections on a Researcher’s Positionality/Multiple “I’s”. In L. L. Rowell, C. D. Bruce, J. M. Shosh, & M. M. Riel (Eds.), The Palgrave International Handbook of Action Research (pp. 613-626). New York: Palgrave Macmillan US This fall I am working on my Masters in Education, the following is my proposal research question and justification.

Proposal Research Question and Justification Area of Interest: Project Based Learning Project Based Learning (PBL) stems from the “paradigm of student-centred learning” (Sambeka et al. 2017). Piaget says that students are inherently scientists who try “to understand the world through meaningful learning as an activity of constructing ideas” (Doppelt 2003). PBL gives students back the freedom to be their naturally inquisitive selves (Doppelt 2003). In PBL students engage in curriculum-based projects in which the product and/or outcome are not provided. The goal is for students to take control of their own learning and for teachers to “guide and advise” (Sambeka et al. 2017) the learning process, rather than lead and instruct. This “transfer of responsibility” occurs through guidance of the teacher who slowly increases the “degrees of freedom for learning” (Doppelt 2003). Many researchers rave about the benefits of PBL; Sambeka, Nahadi and Sriyati state that in PBL students’ “learning is inherently valuable because it's connected to something real and involves adult skills such as collaboration and reflection” (2017). During the 2016/17 school year, my multi-grade 8 to 12 art class completed a PBL project over a four month period. The assignment was to build a functioning bicycle camper. The students were given a list of required bicycle camper features, a $200 budget that they were responsible for tracking, and access to a variety of tools. After reviewing some bicycle camper examples, and learning tool safety the students were set free to build their campers in teams. In addition to myself, I had two parent volunteers with building experience to help guide the students and ensure safety. Sambeka et al. says that “one of the key elements of 21st century learning is learning and innovation skills” (2017), just as is identified in the Core Competencies of BC’s renewed curriculum: Communication, Thinking, Personal and Social. PBL is one of many learning strategies that students and teachers can utilized to achieve such skills. Research Problem: Assessment of Project Based Learning Traditional assessments such as testing, is not an effective way to evaluate PBL. Sambeka et al. states that in order to assess any PBL activities “teachers have to implement an authentic assessment…because project learning is authentic learning” (2017). Sambeka et al. defines authentic assessment as “a form of assessment in which students are asked to perform real-world tasks that demonstrate meaningful application of essential knowledge and skills” (2017). It is comprehensive in that it assesses both the input and output as well as the process of learning (Sambeka et al. 2017). The purpose of this study is to develop a PBL opportunity for my students which encompasses an authentic assessment. To do this I plan on reflecting on the bicycle camper project and researching current literature. Research Question How does teacher reflection of assessment affect the development of PBL? Works Cited Doppelt, Y. (2003). Implementation and assessment of project-based learning in a flexible environment. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 13(3), 255-272. doi:10.1023/A:1026125427344 Sambeka, Y., Nahadi, & Sriyati, S. (05/30/2017). AIP conference proceedings: Implementation of authentic assessment in the project based learning to improve student’s concept mastering American Institute of Physics. doi:10.1063/1.4983980 Yet again we are confronted with the notion that action research is not considered ‘real’ research. Lather argues that the push by the federal government (Lather is specifying the USA government, but it is parallel to the issues seen in the Canadian education system) to use the ‘gold standard’ in educational research is not good enough (2006). Contradicting the ‘gold standard’ Lather says that educational research should be “about saying yes to the messiness, to that which interrupts and exceeds versus tidy categories” (2006). The fact is, educational research just does not fit into a neat little box, but that is not to say that it has no bounds. Anfara and Mertz suggest that while educational research may not appear to fit under traditional theoretical frameworks, qualitative studies has its place. In opposition to traditional theoretical frameworks, in qualitative studies “the development of a theory or comparison with other theories comes after the gathering and analysis of data.” (Anfara & Mertz 2006). It is the development of such theories, whether contradictory or consistent with other theories, that moves research forward.

Works Cited Anfara, V. A. & Mertz, N. T. (2006). Introduction. In V.A. Anfara & N.T. Mertz (Eds.), Theoretical frameworks in qualitative research (pp. xii-xxxii). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Lather, P. (2006). Paradigm proliferation as a good thing to think with: teaching research in education as a wild profusion. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 19(1), 35-57. doi:10.1080/09518390500450144 The value of the Tri-Council Policy Statement course on research ethics (TCPS 2) is “of respect for human dignity” which is “expressed through the three core principles”: 1) Respect for Persons, 2) Concern for Welfare and 3) Justice. As a researcher it is our obligation to fulfill these principles, however, Manzo and Brightbill bring up an excellent point that the standard policies that govern the Research Ethics Board (in the USA this is termed the Institutional Review Board) do not suit Participatory Action Research (2007). In order to have human subjects as part of a research study, the researcher must act in an ethical way that protects the human subjects, ultimately the REB and IRB sees that the only way this can be done is to have neither a negative nor a positive influence on the participants (Manzo and Brightbill 2007). Participatory Action Research (PAR) on the other hand aims “to instigate change and to create benefits for participants” (Manzo and Brightbill 2007). Should researchers have the power to make these decisions? How does one know whether their perceived positive impact will in fact benefit the people involved? Although PAR attempts to answer this by including the participants in the research process, do we still run the risk of unintentionally making a negative impact on innocent bystanders? As practitioner researchers using PAR this brings about a moral dilemma.

Works Cited Battiste, M. (2008). Research ethics for protecting indigenous knowledge and heritage: institutional and researcher responsibilities. In Denzin, N. K., Lincoln, Y. S. & Smith, L. T. Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies (pp. 497-510). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi: 10.4135/9781483385686 Manzo, L. C., & Brightbill, N. (2007). Toward a Participatory Ethics. In S. L. Kindon, R. Pain, & M. Kesby (Eds.), Participatory action research approaches and methods: connecting people, participation, and place. (pp.33040) Oxon: Routledge. According to Cochran-Smith and Lytle, action research falls under the “umbrella” of practitioner inquiry (2009). Action research allows practitioners to inquire from a place of “neither theory nor practice alone but from a critical reflection on the intersection of the two” (Cochran-Smith and Lytle 2009). In opposition to traditional research methods, action research is unique in that it allows for practitioners to play both the role of the researcher and the subject. From their unique position the practitioner is able to analyze simultaneously both their own practice alongside students learning (Cochran-Smith and Lytle 2009). Unfortunately action research is often thought of as an inferior form of research, however, this should not dissuade practitioners, as the benefits to one’s own practice are immeasurable. An inability to be objective is one of the criticisms of action research, however, according to action research this is in fact one of the main benefits. The practitioner’s dual role allows them to inquire subjectively which is key to action research. In fact according to Friedman and Rogers action research begins with “understanding participants’ perspectives” (2009).

Works Cited Friedman, V. J., & Rogers, T. (2009). There is nothing so theoretical as good action research. [Article]. Action Research, 7(1), 31-47. doi: 10.1177/1476750308099596 http://journals.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/doi/abs/10.1177/1476750308099596 Cochran-Smith, M. & Lytle, S. (2009). Teacher research as stance. In Noffke, S. E. & Somekh, B. The SAGE handbook of educational action research (pp. 39-49). London: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi: 10.4135/9780857021021 One summer day a 9 year old boy in East LA created his first arcade game out of a left over cardboard box from his dad's shop. Soon his single arcade game grew into a fleet, all made from cardboard boxes and a lot of imagination. Watch Caine's inspiring story. After the making of this film, Caine's Arcade quickly became famous! A scholarship fund was made in Caine's name and has raised nearly $250,000 for his college fund. What started out as simple fun has exploded into an international movement. For more information you can follow Caine on his website.

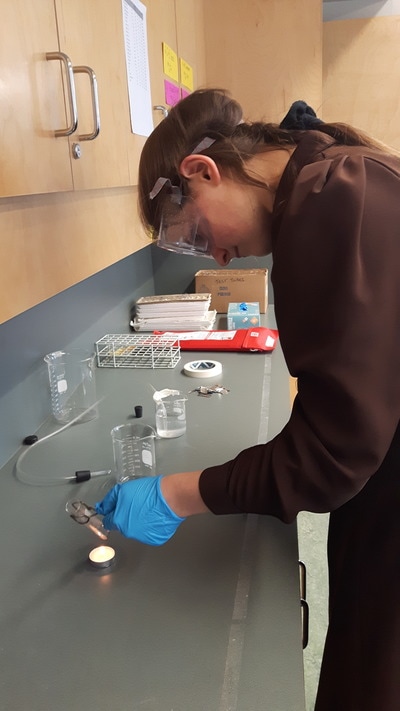

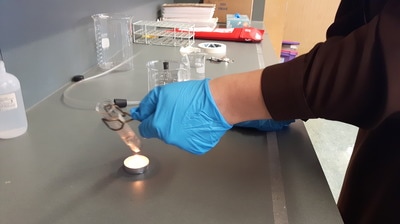

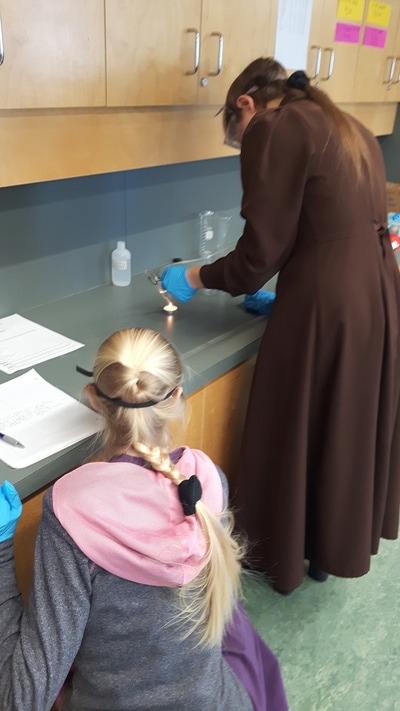

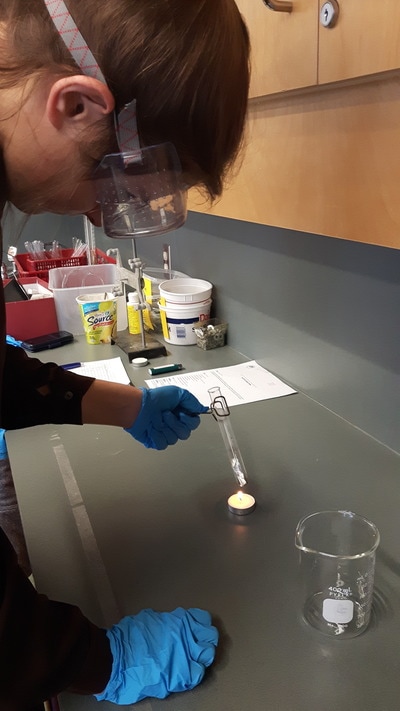

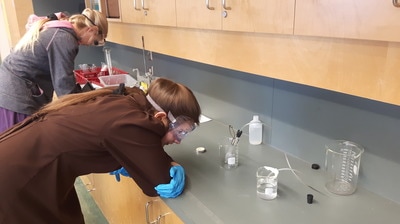

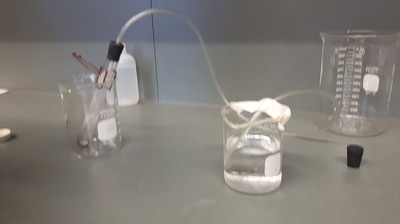

A couple of students came in today to find out what happens to the rate of reaction when the concentration of reactants is altered?

|

AuthorI am Ms. Jennifer Adams, I am a high school teacher in beautiful British Columbia, Canada. Archives

December 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed